First, What Is Lascaux?

Discovered in 1940 in the Dordogne Valley, the original Lascaux cave holds one of the world’s most extraordinary collections of Ice Age art: over six hundred painted animals and more than a thousand engravings, dating back some seventeen thousand years. The cave was opened to the public after World War II, but within two decades, the presence of visitors began to damage the fragile pigments. In 1963, Lascaux was permanently closed.

What visitors experience today at Lascaux II is a meticulous recreation of the caves’ two most celebrated chambers, crafted by artists and scientists with the same care once given to the paintings themselves. Every curve of the rock, every pigment and shadow, has been reproduced in full scale underground, creating an experience that is immediate, convincing, and astonishingly true to the original. Unlike Lascaux IV, which offers a comprehensive museum-style interpretation of the entire cave system, Lascaux II is deliberately intimate. By focusing only on the heart of the site, it gives visitors the closest possible experience of stepping into the original cavern – quiet, concentrated, and astonishingly true to place.

DISCOVERY: FOUR BOYS AND A DOG

History sometimes begins with a simple wrong turn. In 1940, four teenagers and their dog wandered into a hollow near Montignac in the Dordogne Valley. The dog disappeared through a gap in the rocks; the boys followed with a lantern. What they found was not treasure, but something older and stranger: paintings sprawling across the walls and ceilings of a hidden cavern.

Word spread, and soon scholars and photographers descended. For the first time, modern eyes were confronted with Ice Age art not as scattered fragments in museums, but as a vast, continuous environment — a complete world painted onto stone. The discovery quickly became a global touchpoint – but for most of us, cave paintings have only appeared in unexpected places: on a classroom wall chart, in a dog-eared textbook, or flickering across a classroom TV during a grainy documentary.

A TIMELINE ETCHED IN STONE

1940

Discovery of the caves by Marcel Ravidat and friends

1948

Opened to the public; thousands arrive weekly

1963

Closed to protect the paintings from damage caused by humidity, CO₂, and fungi

1983

Lascaux II replica opens, meticulously recreated

2016

Lascaux IV, an expanded museum and digital interpretation center, opens

Stepping Into the Darkness

The entrance to Lascaux II is purpose-built, set discreetly into the Dordogne hillside. You don’t descend into a wild cavern but into a carefully crafted reconstruction – one that mirrors the contours and atmosphere of the original.

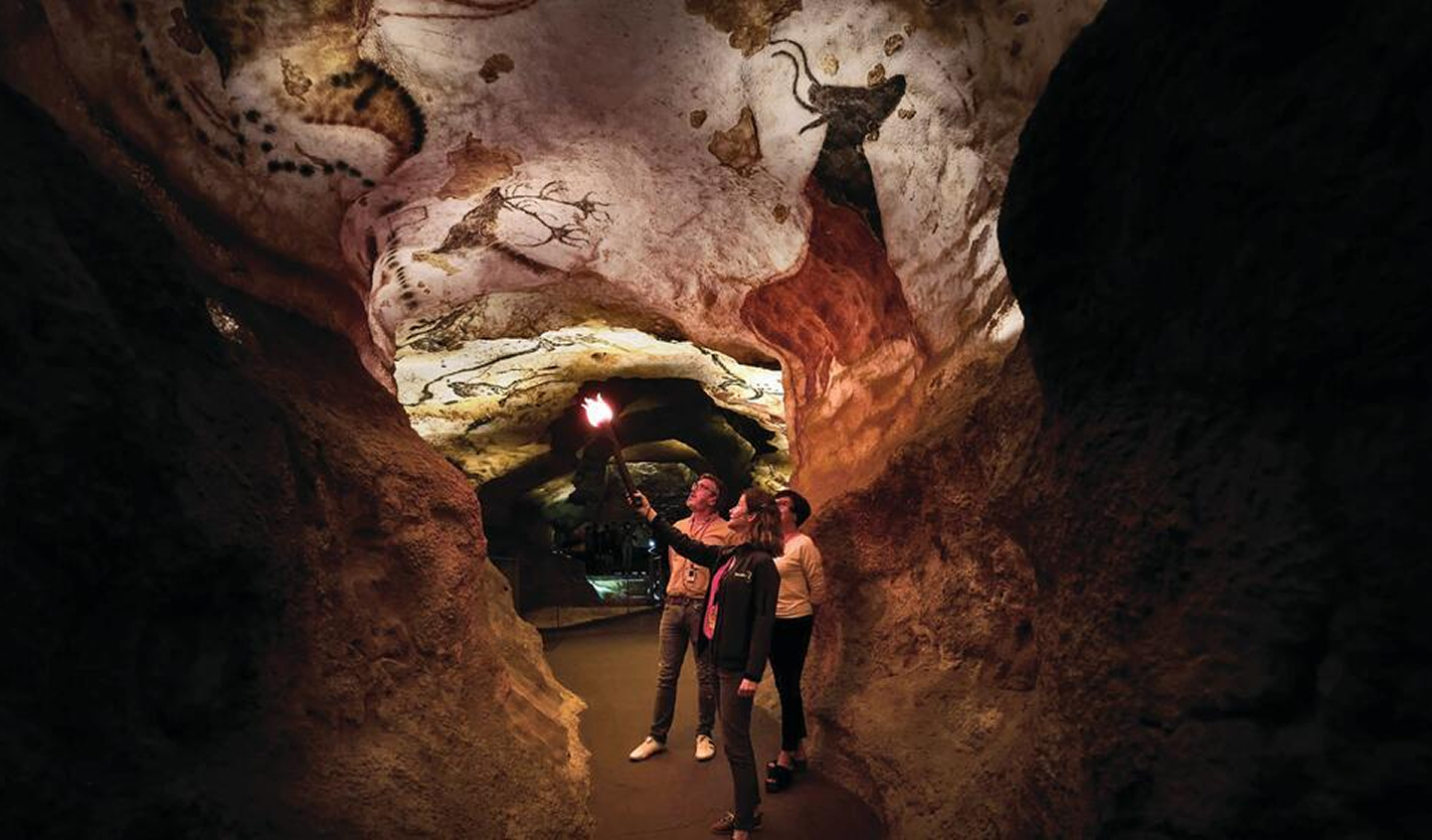

The air inside is cool and faintly damp, the hush immediate. Guides use handheld lamps to cast shifting light across the walls, recreating the flicker of fire that once revealed the art. Shapes emerge from shadow: a horse with its neck arched, a bull with its horns lowered, stags branching upward across the rock. The experience is deliberately staged to echo how the art would once have been seen.

A private visit shifts the mood even further. There’s no glass in front of the walls, no crowd pressing close, no noise competing with the silence. It’s just you and the paintings, re-created with extraordinary precision, on their own terms

Walking Into the Chill

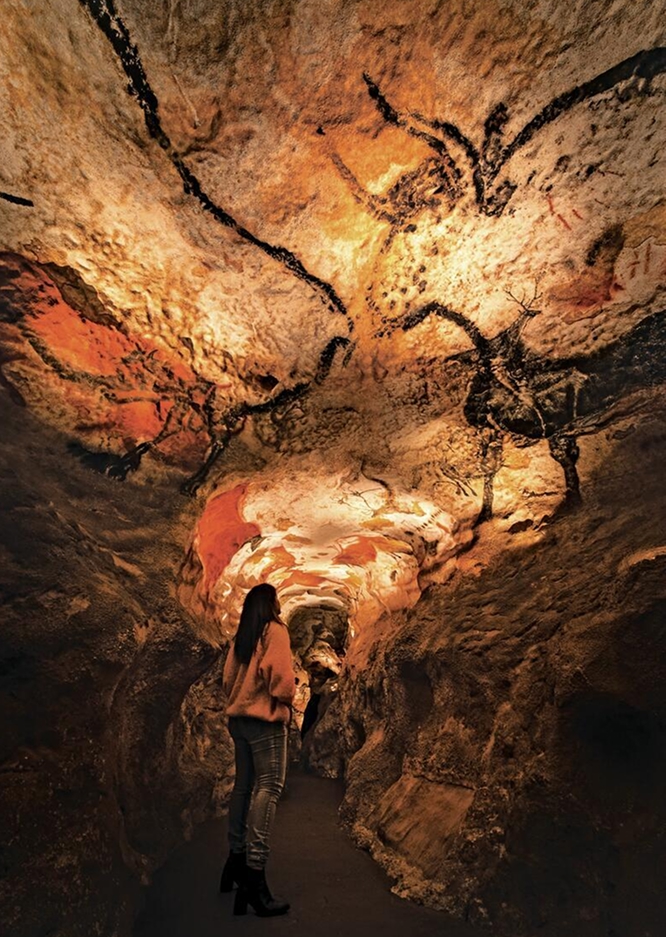

Inside Lascaux II, the cave walls curve and narrow exactly as they do in the original. Ceilings rise and fall, spaces feel alternately tight and expansive. Some chambers brim with overlapping figures; in others, a single animal waits alone in the stone.

The sense of scale is surprising. Horses run in sequences, bison crowd together, stags stretch upward with antlers too large to be real but balanced in motion. The colors – ochre, black, deep red – are drawn from iron oxides, charcoal, manganese. Simple materials, re-created with absolute fidelity.

What strikes you most is how assured it all feels. These weren’t experiments. They were decisions. And in another chamber, a single handprint appears among the animals – not a symbol or a scene, just a presence, pressed into stone seventeen thousand years ago, now preserved for us here.

Did You Know?

More than 600 animals and 1,500 engravings cover the cave walls.

Lascaux has been called “the Sistine Chapel of Prehistory.”

Some researchers suggest the paintings may mirror star constellations.

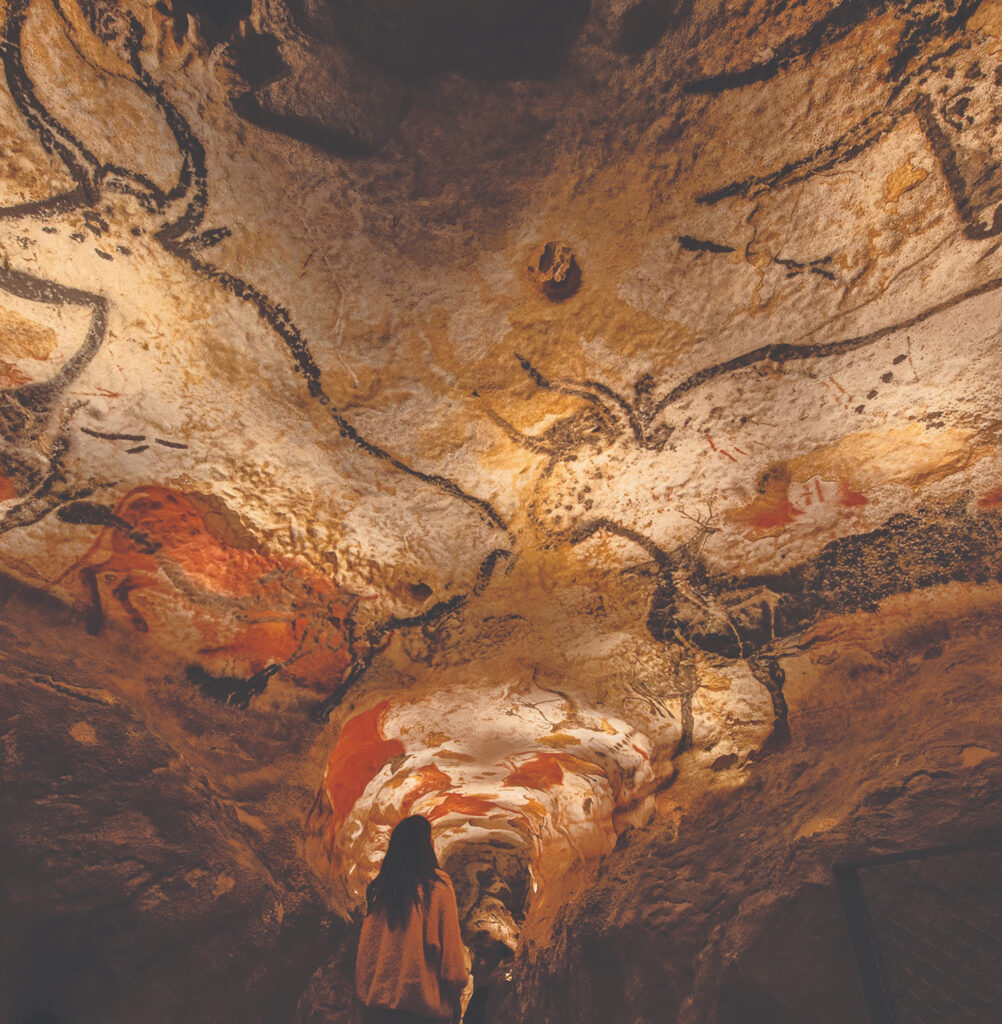

The Hall of the Bulls

Perhaps the most famous chamber, the Hall of the Bulls, is overwhelming in its density. Horses run in multiple directions, their outlines overlapping. Four massive bulls dominate the space, one stretching more than seventeen feet across. Their bodies are powerful and imposing, horns exaggerated, yet their lines are economical and confident, almost casual.

In the dimmed light, the chamber reveals itself as it once did: figures that shift with every step, shadows that hide and reveal. What comes through is not grandeur but presence – the sense of people working methodically, image by image, until the stone became the story.

“To stand beneath the bulls in silence is to feel both small and connected.”

Why It Matters

What stands out in Lascaux II is not only the artistry of the original works but the precision of the reconstruction. It is no substitute, but it allows us to encounter the Ice Age painters’ vision without endangering the fragile originals.

The walls aren’t marked with random images – they’re composed with rhythm and balance. Animals overlap deliberately, their proportions adjusted for effect, their movements caught mid-stride.

The paintings aren’t primitive sketches. They’re complex works: layered, shaded, composed. They don’t just depict animals; they capture how they move, how they gather, how they scatter.

What you realize standing here is not nostalgia but continuity. The instinct to create, to record, to interpret – it’s older than history, older than language. And that is why it matters: Lascaux II preserves for us the experience of Lascaux itself, reminding us that imagination is not a modern invention, but the oldest human inheritance we have.

Preservation and Privilege

By the early 1960s, thousands of daily visitors were taking a toll. Carbon dioxide, humidity, even the heat of human bodies began to damage the pigments. Mold and algae followed. In just a few decades, the art faced more risk than in the previous seventeen thousand years.

In 1963, the caves were closed to the public. Replicas followed, each more sophisticated than the last. Lascaux II was the first, and remains the most intimate, designed for visitors to experience the art without compromising the original.

That limitation is part of the experience. You enter not just as a viewer, but as a caretaker of memory, entrusted to carry forward what can no longer be seen directly.

Beyond the Cave: The Dordogne

Your Lascaux visit is only one layer of the Dordogne. The river winds between cliffs and castles, past medieval towns like Sarlat-la-Canéda. Markets brim with walnuts, truffles, and duck. Renaissance manors rise over farmland, and vineyards stretch across plateaus.

This is a region where eras stack visibly on top of one another – prehistoric, medieval, Renaissance, modern. Lascaux is the anchor, but the story doesn’t end at the cave mouth.

The Last Word from Lascaux

The painters of Lascaux lived seventeen thousand years ago, yet their work is still clear – what remains isn’t accidental. It reflects intention. Their world is gone, but the drive to make meaning endures.

That’s why the caves matter – and why Lascaux II matters. To step inside isn’t to travel backward in time, but to recognize that the instinct to make meaning – scratched and painted onto stone – is the same force that still drives us today.

“The paintings remind us that creativity is the oldest human inheritance.”